The Site and the Excavations

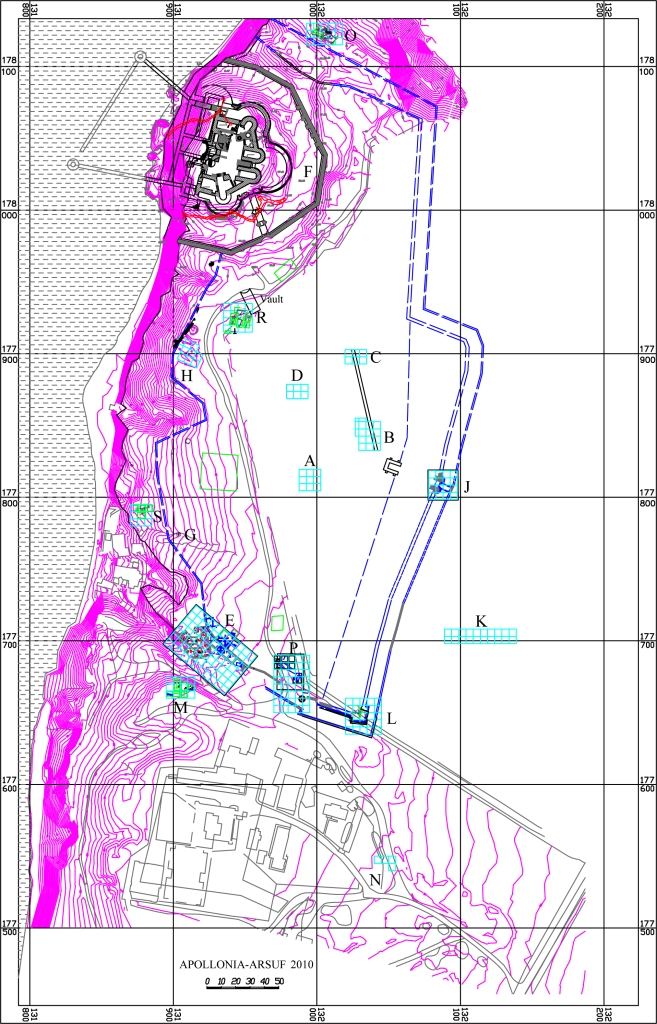

Apollonia-Arsuf is located in the northwestern part of the modern city of Herzliya on a kurkar (fossilized dune sandstone)

ridge overlooking the Mediterranean shore (Fig. 1). The site lies 17 km north of Joppa and 34 km south of Caesarea. The

ground of the eastern part of the site rises 35 m above sea level, and from there gently slopes down to the west, to about

20 m above sea level (Fig. 2).

The first systematic excavations at Apollonia-Arsuf were carried out in 1950, north of the Medieval city wall on behalf of

the Israel Department of Antiquities, first by I. Ben-Dor and then by P. Kahane. The former excavated several trial trenches

down to virgin soil, from which he ascertained that

|

|

Fig. 1 - Apollonia-Arsuf, looking north |

|

this part of the site never served as a residential area. He discovered a

series of three different types of winepress, which indicate that the site served as an industrial quarter of the Byzantine

city. Kahane worked on

|

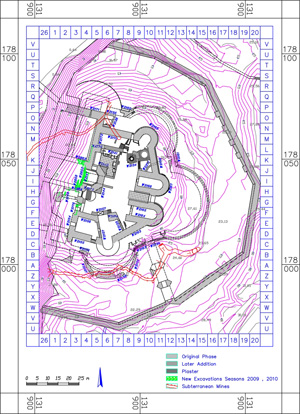

Fig. 2 - Site plan

|

|

a larger scale, throughout the entire area, in six different

places, three of which provided substantial architectural remains

(Areas a, b and c). The excavator's main discoveries included

three types of structures belonging to three different periods,

Late Roman tombs, Early Byzantine oil presses and Late Byzantine

/ Early Islamic raw glass furnaces. In 1962 and 1976, following

development works carried out southeast of the Medieval city

gate (Area K), a polychrome mosaic floor and several bases of

columns, located along an east-west line, were uncovered, all

belong to a Byzantine church.

The first large-scale excavations at Apollonia-Arsuf were carried

out in 1977 by I. Roll who directed seventeen seasons of excavations

at the site until 2004. The 1977 season was a salvage excavation

on behalf of the Israel Department of Antiquities and Museums,

whereas only in 1982, the project became an academic excavation,

on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University.

The 1996 season was a contract excavation, initiated by the

legal owner of the entire area of Apollonia-Arsuf, the Israel

Lands Authority.

The request was to undertake a series of trialexcavations in the area that extends from the Crusader city-gate (Area J) to the east, with the purpose of determining the maximum extension of the ancient site, and defining its eastern limits. |

| The 1998, 1999, and 2000 seasons excavations were organized as a joint venture of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University and the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul of Porto Alegre, Brazil with the financial backing of the Municipality of Herzliya and the Israel Nature and National Parks Protection Authority. |

In 2009 a nineteenth season of excavations at Apollonia-Arsuf was made. It was a fruit of collaboration between Tel Aviv University and Brown University, Division of Engineering researchers (headed by David B. Cooper), partially funded by the National Science Foundation. Brown University researchers were responsible for computer vision research (digital archaeology), documenting of the site excavations,archaeological remains paradigm shifts for the promotion of the archaeological research in Israel and beyond.

In 2001

the site of Apollonia-Arsuf became a national park.

In 2004 the site was formally recognized as one of the

100 most endangered world monuments by the World Monuments

Fund. In 2006 it was included in the tentative list

of world heritage Crusader castles by UNESCO. In 2007

it became the case-study of a National Science Foundation

grant, titled III-CXT-Core Large: Computer Vision Research:

Promoting Paradigm Shifts in Archaeology (Grant #0808718).

All these naturally emphasize the importance of continuing

archaeological excavation and conservation (Fig.

3).

|

|

Fig. 3 - Crusader castle, looking northeast |

|

|

Periods of Occupation

The site of Apollonia-Arsuf was occupied as early as the Chalcolithic

period and the Iron Age II but it is in the context

of the Persian period that Apollonia-Arsuf became a

coastal urban center, under Sidonian hegemony. We learn from

the tomb inscription of Eshmun'azor 2nd, king of Sidon of

the late 6th century BCE, that the Persian (Achaemenid) king,

granted him Dor and Joppa, the mighty lands of grains in the

Sharon Plain. This statement actually infer that the entire

geographical unit of the Sharon Plain was in Sidonian hands,

most probably as tribute for the participation of his fleet

during the first Persian military campaigns to Egypt. Another

historical reference that implies on the site's administrative

status is the Periplus of pseudo-Scylax (4th century

BCE), stating that both Dor and apparently Joppa are under

Sidonian suzerainty. It seems thus that throughout its existence

under Achaemenid rule Apollonia-Arsuf was subject to the Dor

Province. Being the main city and haven of the southern Sharon

Plain it became the chief commercial and probably industrial

centre of the region. The town's dwellers, the Phoenicians,

left their linguistic mark on the city by naming it after

one of their gods, that is Resheph. Even though the

city's Phoenician name was not attested in writing and its

conquerors and foreign inhabitants quickly renamed it, it

nonetheless was not forsaken for at some later point, the

Arabs reinstated the Semitic name, that is Arsuf which

may suggest that in Persian times the site was named Arshoph.

The settlement at this time is represented by two strata over

an area of less than 20 dunams. These strata contain minor

architectural remains, presumably domestic in nature, in Area

H and a large refuse pit in Area D. The finds, ranging in

date between the late 6th and late 4th centuries BCE, include

mostly common pottery but also imported wares, fragments of

male and female terracotta figurines and a fairly

|

Fig. 4 - Totenmahlrelief |

|

large number of Sidonian coins. A unique discovery is a 4th century BCE

Pentelik marble relief (11 x 15 cm) of the Totenmahl (funerary banquet) type (Fig. 4). The scene depicts a bearded man in front

view, dressed in a mantle and reclining on a couch (kline). In his right hand is an elongated object, probably a rhyton, while his

left hand holds another object which may be a phiale. Opposite the man, seated at the left end of the couch, is a woman in profile

with her hair bound in a sakkos, wearing a chiton and resting her feet on a footstool. In her left hand is a cup-like object, while

her right hand apparently rests on her thigh. Behind the woman, two smaller figures stand in profile, facing the reclining man, their

hands raised as if in worship: a bearded male and a veiled female, both dressed in a chiton. At the top left comer is a bust of a

horse within a frame. At the lower right comer, the lower body of a krater is visible, next to an offering table with turned legs.

Underneath the table, a coiled serpent stretches

|

towards the reclining man. To the left of the table there is

a pedestal-like altar. The presence of such an object at Apollonia-Arsuf

should be attributed to the connections of the town with the

Greek world (especially Attica), as is demonstrated by other

archaeological finds retrieved from the site. The relief's connection

with a cult of a hero or the heroised mortal dead strongly suggests

the presence of Greek individuals who practiced such a cult

at the site. Whether this dead hero was buried at the site or

in his homeland is impossible to determine, although one cannot

exclude the presence of a Greek family who settled at the site

and buried one of its commemorated members.

It is during the Hellenistic period that the site was

renamed Apollonia. We have evidence that the Phoenician god

Reshef was already identified with the Greek deity Apollo as

early as the 4th century BCE. It is thus not surprising to learn

that the site was affected by the region's Hellenization or

rather lingual revolution; Arshoph became Apollonia,

Dor became Dora, and Joppa became Ioppe.

Archaeologically, the settlement maintained the size of that

of the Persian period and is represented by a single stratum

with minor architectural remains in Area H, and a refuse pit

in Area D. The finds, ranging in date between the late 4th and

late 2nd centuries BCE, mostly include common pottery but also

imported wares and stamped amphora handles. All indicate that

the site was abandoned in Early Hasmonean times, apparently

in the frame of Alexander Jannaeus territorial expansions in

the Sharon Plain. The poor preservation of both the Persian

and Hellenistic strata at the site is due to the intensive building

activities in later periods.

It is in the Roman period that the site is first mentioned

in the historical sources. Flavius Josephus lists Apollonia

among the cities belonging to the Jews under Alexander Jannaeus

together with Joppa. Pliny and Ptolemy list Apollonia among

the coastal cities of Iudaea-Palaestina. The depiction of Apollonia

on the Peutinger map along the coastal highway, between Joppa

and Caesarea, indicates that it served as an official leg on

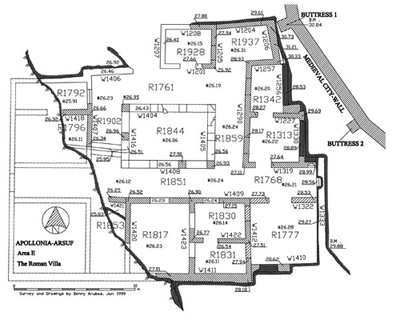

the country's Roman imperial road network. The most significant

remains of the Roman period occupation at the site are undoubtedly

those of a typical Roman villa of the peristyle type uncovered

in

Area E in the south part of the site. Located against the southern

flank of the Early Islamic city wall, the villa was built on

a platform carved out from the natural sandstone rock. Measuring

some 21.5 x 24 m, the building was laid out in the precise directions

of the four cardinal points. As the western facade of the dwelling

faces the sea, it seems clear that this was a villa maritima,

which could have belonged to a foreign rich merchant or a local

magnate who may have undergone Romanization (Fig. 5).

|

|

A peristyle courtyard occupies the center of the building, which

is surrounded by square piers supported by a stylobate. To its

south is a long corridor that crosses the entire building from

west to east. In the upper parts of two of the walls at the

eastern end of the corridor are plastered niches that recall

the lararia of the typical Italian dwelling. Three shorter

corridors surround the other sides of the courtyard. The walls

of the villa were remarkably well built, with large kurkar

ashlars set into grey cement, which was the typical construction

method of the Roman period. On the whole, the structure was

built according to the standard of the Latin foot (pes),

which measures about 0.3 m. The thickness of the inner walls,

with the exception of the walls of the peristyle, ranges between

0.4 and 0.45 m, corresponding to one

cubitus (0.45 m).The central courtyard, |

|

Fig. 5 - The Roman villa, aerial view and plan |

|

with interior dimensions of ca. 6.45 x 3.85 m, corresponds to

22 x 13 pedes; and the corridors measuring 2.4 m on average

correspond to 8 pedes. Overall, the interior dimensions

of the rooms seem to correspond to the standard of the Latin

foot as well. The villa's design as an unfortified and isolated

open dwelling facing the Mediterranean Sea was previously unknown

in Iudaea. |

Fig. 6 - Artistic reconstruction of the Roman villa

|

|

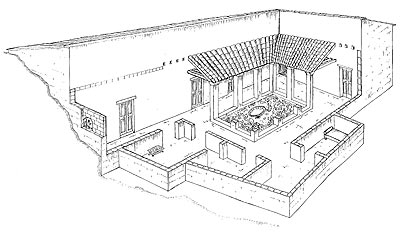

This private structure, built to emphasize leisure, privacy,

tranquility, social status, and economic wealth, clearly reflects

an aspect of the Romanization of the coastal plain of Judaea

that was apparent in the late 1st century CE (Fig. 6).

In a later phase of the villa's use, the entrances to several

rooms were intentionally blocked in a rather careless manner,

perhaps indicating that several of the living rooms had been

turned into storage rooms for more modest owners. The entire

complex then suffered a sudden and violent destruction, probably

caused by a devastating earthquake in 113/114 or 127/128 CE. |

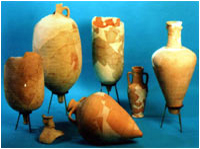

Most of the finds from the villa came from the later phase

and include table, cooking and storage vessels, and local and imported lamps (Fig. 7). Smaller quantities of stone and glass

vessels, bone objects and human and animals figurines were also discovered.

Fig. 7 - Selection of pottery vessels from the Roman villa later phase

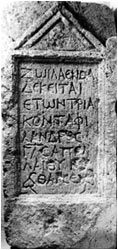

Another important Roman find is a gravestone with a Greek inscription, that is presently housed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

It has a rectangular frame, surmounted by a pediment with acroteria at the corners and a rosette inside the tympanum. It can

be translated as follows: "Here lies Zoila, thirty years of age, who loved

|

her husband. (Died in the year) 233, 26 of Apellaios.

Courage" (Fig. 8). As previously mentioned, Flavius Josephus mentions Apollonia as one of the cities inhabited anew by the order

of Gabinius, and the year 233 apparently refers to the Gabinian era which started in the year 57 BCE, indicating that 176 CE is the

probable date of this inscription.

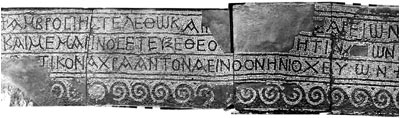

A polychrome mosaic floor and several column bases placed along an east-west line were uncovered in 1962 and 1976 in Area K.

These elements belonged to a Byzantine church, of which only a part of the nave has survived. The preserved part of the

pavement is decorated with stylized geometric and floral patterns, framed interwoven motifs, and birds inside round running

medallions. The most impressive part of the mosaic floor is a three-line Greek inscription framed in a tabula ansata, intended to

be read when facing east. The inscription is partly damaged but the following reading is suggested: "I am a church better than

ambrosia and nectar, and Marinos erected me exalting God-extolled-for-His wisdom and ever ruling his pure and mystic spirit"

(Fig. 9). The inscription was formulated in dactylic-hexameter verse and has a clear poetic character. Its metaphoric language

was meant to make a declaration - ostensibly by the church itself - that it was built by one Marinos who was well acquainted

with Classical Greek culture. Moreover, the words "ambrosia" and "nectar" point to a tradition reminiscent of the highest

achievement of Greek literature, that is, the Homeric epic. However, the inscription also emphasizes, in a very clear manner, the

superiority of the Christian Church over the Classical tradition,

|

|

Fig. 8 - Gravestone of Zoila |

|

which resulted from the Church's ruling wisdom, pure nature,

and mystic spirituality. The decorative pattern of the compound and its inscription indicate a 5th-6th century CE date. This

church may have served as the seat

|

Fig. 9 - Greek inscription of the church's mosaic floor |

|

of the bishops of Sozousa, that is, Byzantine Apollonia. Other architectural remains

attributed to the Byzantine period are confined primarily to a series of industrial installations such as water cisterns, wine- and

oil-presses, primary glass kilns, and others of unclear function. The primary glass kilns, or furnaces, deserve special attention due

to the rarity of these finds. Two glass furnaces

|

|

were reported to have been excavated as early as 1950 by Kahane, but were

attributed an Early Islamic date, another glass furnace was discovered during the 2002 season in Area N (Fig. 10), and an

additional furnace was discovered during the 2006 season in Area O, but this may already has been noted by Kahane in 1950. It

|

|

immediately became apparent that this furnace is an isolated ashlar-built structure consisting of two parts: a melting chamber

(of about 5.0 m x 3.8 m); and a firing area (of about 3.8 m x 1.6 m) with two conical-shaped firing chambers that opened onto

the melting chamber. A large glass slab (about 4.45 x 2.95 m) was found on the melting chamber floor, which was separated from

the firing area by a segmented stone wall. Extracting the slab required the roof of the installation to be dismantled after the

glass had solidified and cooled. This was done by hammering and removing chunks of various sizes, as can be seen by the

dents created on the preserved remains. The entire installation was overlain with fired mud-bricks. The high-quality raw glass

that was extracted was transparent-blue and greenish-blue with a few bubbles. However, the glass from the preserved

northwestern and southeastern corners of the melting chamber was yellowish-green and yellowish-brown, resulting from the

amount of oxygen it absorbed (a high oxygen level leaves a bluish-greenish tinge and a low oxygen level renders a yellowish tinge).

Numerous chunks of raw glass were discovered during the excavations. We may assume that chunks of insufficient weight or

size for trade were discarded; they were probably removed from the slab while it was being extracted. We also found under the

glass furnace a few pottery body fragments from a well-known type of Palestinian bag-shaped jar of Late Byzantine date. The

firing chambers in the glass furnace from Apollonia-Arsuf were located on the west, and the melting chamber was on the east.

The two firing chambers facing west were open to sea winds, thus facilitating the airflow that otherwise would have required the

use of bellows. The roof of the melting chamber was

|

|

Fig. 10 - Glass furnace of Area N |

probably vaulted, with a few openings (or chimneys) to provide better air

circulation. In the Late Byzantine period, the "crater" stretching between Areas E and M was one of the main dumps of the town of

Sozousa. Some 10 tons of Late Byzantine pottery was retrieved in the excavations of Area E and an additional 13 tons was sorted

from Area M in the 2006 season alone! The pottery, glass, metal, and stone vessels and objects reflect the inhabitants' daily ware.

There are also several burials of the Byzantine period in the immediate environs of the site, notable among them are built cist

tombs that were found undisturbed alongside with a damaged mausoleum.

Reference must be made to other important Byzantine finds that were found at the site during the 1880s:

- A marble statue of a standing eagle with contracted wings, with a monogram that reads ΙΟΥΛΙΑΝΟΣ, apparently referring to the Byzantine emperor Julian (361-363 CE).

- A fragment of a marble relief showing the lower part of two horse legs. This iconographic document, albeit fragmentary, is of great importance because it is directly related to the contentious issue of when and where the common use of horseshoes began.

- A wide limestone lintel of a tomb which bears a Greek inscription that reads "One is the living God. Babas (son) of Maximus, grandson of Kosmas, made the burial monument for Marcellina Justina."

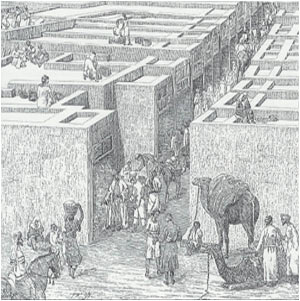

The historical documentation of Early Islamic Arsuf is supported by several archaeological finds. Long stretches of the

city-wall were uncovered in the southern and western parts of the site (Areas E and H) and the earliest finds unearthed in

the inner adjoining rooms date to the reign of the Ummayyad Caliph 'Abd el-Malik (685-705 CE). The initial phase of a market

street, of which a section of some 65 m have been uncovered, was exposed in the eastern part of the site (Areas B and C)

(Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 - Early Islamic market, plan and artistic reconstruction

Various buildings flanking both sides of the street and serving as shops and food-stalls date to the same period.

These finds indicate that Early Islamic Arsuf became a fortified city, with a large part of it having been rebuilt according to

a comprehensive urban plan already at this early stage.

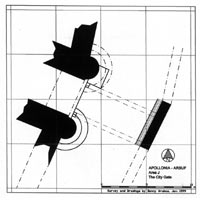

Excavations in the Crusader city-gate (Area J) revealed two construction phases of the city-gate, both from the Crusader period

(Fig. 12). Large-scale excavations were conducted in the Crusader castle (Area F),

|

Fig. 12 - Crusader city-gate, aerial view and plan |

|

exposing practically all the components of

the castle's latest phase (Fig. 13). These include the following elements described from the inside outward: (1) a central irregular

courtyard surrounded by broad halls; (2) the main

|

pentagonal fortification complex, including a gate protected

by two semicircular towers with an additional semicircular tower

on each side in the east, and a donjon and two square corner

towers in the west; (3) an external fortification with a contour

corresponding largely to that of the main fortification but

at a lower elevation and with a wider opening ; (4) a broad,

deep moat bounded by an outer retaining wall; (5) a system of

vaulted halls and retaining walls along the cliff at the western

facade of the fortress, which largely collapsed falling to the

base of the ridge; and, finally (6) a port facility, of which

the foundations of the northern and

Fig. 13 - Crusader castle, aerial view

and plan

southern breakwaters have been preserved. A particularly unique

find published by the Italian scholar S. Paoli in 1733 is the

official seal of Balian of Ibelin's short lordship (1258-1261

CE) found in Malta. Its reproduction shows (Fig. 14)

a fully armored knight brandishing his sword and galloping to

the right on a caparisoned horse. The surrounding inscription

reads: "Ba(lian) d'Ybel(in) s(eigneur) d'Ars(ur) co(n)establ(e)

dou reaume d(e) I(e)r(usa)l(e)m" (= "Balian of Ibelin, lord

of Arsur, constable of the kingdom of Jerusalem"). The other

side depicts a castle with crenellated fortifications, as well

as two corner towers and a gate dominated by a central donjon.

The inscription around it reads: "Ce est le chastiau d(')Arsur"

(= "This is the castle of Arsur"). The reproduced document,

though schematic, provides a unique iconographical representation

of the lord of Arsur |

|

and his castle. In mid-March 1265 CE a large and well-prepared

Muslim army under the personal command of Baybars laid siege

to Arsur. From the Crusader's point of view, Arsur was relatively

well prepared. Its town and castle were strongly fortified,

well-provisioned, and defended by some 2,000 warriors, with

about 270 of them belonging to the Brothers of the Order. Excavations

show that during the Mamluk siege, tons of dirt was intentionally

piled against the interior walls of the Crusader town fortifications,

and buildings built against these fortifications were intentionally

covered with dirt in order to strengthen them. A stone and cement foundation (3-m-wide and 17-m-long) found in Area P

seems |

|

Fig. 14 - Transliteration of Balian's seal

|

|

to

have been built on that occasion and may have been used to convey

ballista machinery. On April 26, 1265 CE, after forty days of

siege, a concerted attack was carried out and the city was taken

by storm. The surviving defenders took refuge in the castle

and continued to fight with superb courage. However, after three

more days of fierce fighting, Muslim warriors took control of

part of the castle's fortifications and were able to raise the

banners of Islam over the walls. The Hospitallers, after having

lost up to 1,000 warriors including 90 knights, asked to surrender

on the condition that the survivors would be free to leave.

Baybars at first agreed but then broke his word and all of them

were taken into slavery. Moreover, he forced the Christian prisoners

to participate in the systematic demolition of their own stronghold.

The entire site of Arsur was razed to the ground and left in

ruins. |

Fig. 15 - Selection of glazed bowls from the Crusader refuse pit |

|

This final destruction is largely attested by thick conflagration

layers and ruins that were uncovered in the excavated areas

all over the fortified site in general, and in the castle

in particular. A unique discovery found in the Crusader castle

is the refuse pit of the besieged containing numerous local

and imported pottery vessels (Fig. 15), plain and luxury

glass vessels, metal and stone artifacts. The importance of

this assemblage lies in its absolute dating, March-April 1265

CE.

Underwater Archaeology

A series of underwater surveys were conducted

at the seaside remains of Apollonia-Arsuf by E. Grossmann.

An underwater inspection team of the Israel Antiquities Authority

headed by E. Galili also undertook sub-aquatic activities

there. These surveys show that Apollonia-Arsuf possessed two

maritime installations; a sheltered, partially |

|

built anchorage and a built harbor. In the sheltered anchorage

opposite the fortified city the eastern face of the sandstone

reef was carved and smoothed. Massive conglomerates, large

blocks and ashlar stones were placed on the reef and near

it, which denotes its role as a man-improved breakwater. In

the anchorage area, a large number of stone anchors of various

types were found, as well as sounding leads, and vessels and

nails made of bronze. The more impressive finds include fragments

of a life-size bronze statue of a male, a bronze statuette

of the goddess Minerva, a lead strip with Latin letters, and

a carved marble vase. The pottery assemblage found in the

anchorage include sherds from the Persian, Hellenistic and

Roman periods, but most of it are fragments of storage jars

and pithoi of Byzantine times. This brings to Grossman's conclusion

that Apollonia, an industrial centre with overseas trade connections,

had two contemporaneous maritime installations in Byzantine

times; one for international trade and the other, smaller,

serving local fishermen and coastal trade. This also indicates

that the activity of the anchorage reached its peak in the

Byzantine period, that is, at the same time when the city

of Apollonia-Arsuf reached its largest expansion. In the east

of the anchorage near the coastline, the remains of a large

structure were surveyed, which included large ashlars, as

well as marble and granite columns. From the large quantity

of Byzantine storage jar fragments found there, it seems that

the building functioned as a Byzantine maritime storehouse.

During Grossmann’s survey of the built harbor located

at the foot of the Crusader castle, mortar samples from the

jetties were subjected to chemical tests and analyzed. The

tests show that, although the jetties proper date to the Crusader

period, their foundations were laid much earlier, in Byzantine

times. Moreover, the foundations of the northern pier seem

to have been built in a way similar to the harbor building

method described by Vitruvius (V, 12, 2–6). It is worth

noting that the entrance to both maritime installations (the

sheltered anchorage and the built harbor) open towards the

southwest. The entrance to the anchorage is a natural opening

in the sandstone reef, whereas in the built harbor it is clearly

man-made. This southwest location for the entrances differs

radically from the other harbors in Palestine, both past and

present, where the entrance faces northwest. This is done

to prevent the south-to-north long-shore current, which is

prevalent the Eastern Mediterranean coast bringing with it

sediment from the Nile Delta, from entering the harbors. However,

it seems that at Apollonia-Arsuf, the opposite (southwest)

location for the entrance was preferred, with the idea of

permitting the entry of the long-shore current into the harbor.

This can be explained by a geological observation of three

nodal points along the Israeli coast, one of them close to

Apollonia-Arsuf, where the sea current reverses and runs in

a southerly direction. Most probably also in antiquity the

current along this shore ran in the same, reversed, direction,

this being the explanation for the unusual placing of the

harbor entrances facing south, for the purpose of de-silting

by natural current action. Alternatively, a more sophisticated

rationale may have been to counteract seaborne sedimentation

in the harbor and allow current-driven de-silting of its basin.

In this case, the gaps left across the foundations of the

northern pier by wooden forms (placed there in compliance

with the Vitruvian method) could have served as flushing channels.

If so, it is not clear at all whether the system worked at

the time or not. Today both installations are partially silted

up with sediments washed in from the sea, awaiting systematic

excavations.

Recent Discoveries

and Future Goals

Our main recent discovery (2009)

came from Area O in the north part of the site, where a large

mosaic floor winepress (9.8 x 7.5 m) was uncovered with a

Greek inscription in the center of its treading floor. The

inscription reads: “One God only, help / Cassianos together

with (his) wife / and children and everyone.” The inscription's

formula and the finds we discovered during excavations in

the area point to Samaritan ownership of the complex in Byzantine

times (5th-6th

centuries CE). Although the inscription

was actually uncovered during the last season of excavations

(August 2006), it was only now that we were able to identify

the complex which it served (Fig. 16). Such

dedicatory inscriptions are mostly known from Samaritan cult

buildings (synagogues); it is possible that the winepress

may form part of a larger structure of a public nature associated

with cultic activity. The winepress' settling (fermentation)

pit (about 3 x 2.2.5 m) is among the largest ever discovered

in Israel. Based on the archaeological evidence the winepress

ceased to function in the first half of the 6th century

CE (possibly in relation to the Samaritan revolt [529 CE]).The

winepress was damaged by an earthquake (apparently that of

749 CE), that is after its abandonment.

Fig. 16 - Area O – A Samaritan

Winepress

Fig. 16 - Area O – A Samaritan

Winepress

In the Crusader castle (Area F), which is

the prominent architectural complex of the site, 2009 and 2010 excavations

were focused on the western part on top of the coastal cliff,

in order to expose subterranean complexes and remove part

of the dirt load from the cliff in order to facilitate future

arrangements for better rainfall drainage. The excavations

uncovered parts of castle’s western façade and

a series of subterranean halls aligned in a north--south axis. These are yet to

fully exposed (Fig. 17). Evidence

for post-destruction (1265 CE) occupation in this area is

already apparent.

Fig. 17 - Area F: A Crusader decorative item (showing the mutilated head of a horned monster) retrieved from fills of the castle western façade

|

Area R which was opened in 2009 is located in the centre of the medieval walled town. The idea to open the area was based on the site plan drawn by the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1874 , where a large vault is shown. Excavations in 2009 uncovered a large structure with a paved white mosaic floor adjacent to the vault. Excavations in 2010 made a considerable progress in the understanding of the building and its function. It appears that the excavated remains of 2009 formed part of an industrial installation of the Byzantine period that was later incorporated in a building of the late Crusader period (13th century CE). This building was partially uncovered. Its original foundations comprises of three rooms; two on the south and one on the east part of the excavated area. The two rooms on the south were found abandoned with complete and restorable pottery and glass vessels on their floors (Fig. 18), whereas the one on the east probably formed part of the courtyard and it revealed paved working surfaces and an intact clay oven (tabun). The upper layers we excavated in the Byzantine installation which later on became a refuse pit included pottery and glass vessels of the Crusader period (12th-13th centuries CE), whereas the lower layers included pottery and glass vessels of the Early Islamic period (8th-11th centuries CE). Still the only physical connection between the later building and the installation can be placed in the mid-13th century CE based on the pottery and glass evidence; it is likely that the building was abandoned in the context of the Mamluk occupation and destruction of the site (March-April 1265).

|

|

Fig. 18 - Area R: An assemblage of Crusader pottery vessels from the building floors

Area S is located in the far western end of the site adjacent to the western Early Islamic city wall. Excavations uncovered the remains of the wall, as well as its foundations. They also uncovered a casemate of the wall whose floor was partially paved with blocks of stones. The floor was dated based on the pottery evidence to the Early Islamic period (8th-9th centuries CE). Earlier remains (namely industrial installations) dated to the Late Byzantine period that occupied the area prior to the foundation of the Early Islamic fortification system were also unearthed. These were appended by a modest assemblage of decorative architectural items dated to the Late Byzantine period that were found out of context in the excavated area. These items point to the possibility that the area to its east, which is much elevated, occupied a public building or a manor house.

|

|

In Area L, the southwestern corner tower

of the Crusader town fortifications, we uncovered the fortification

system of the Crusader town on top of the fortification system

of the Early Islamic town; both were in fact constructed upon

Byzantine architectural remains.

In Area M, in the south part of the site,

which we opened in 2006 and excavated down to virgin soil

uncovering a very large 6th-7th centuries CE refuse

pit and a 4th-5th centuries CE hoard of bronze coins.

The results of the recent seasons provide

a better understanding of the site and in particular the social

and occupational history of the Early Byzantine and Late Crusader

periods.

The Apollonia-Arsuf excavation is an on-going

research project. We intend to continue excavations at Apollonia-Arsuf

in order to better understanding the site's economic basis

and political affinity, as well as its cultural and economic

interactions with other Mediterranean centers during its periods

of successive occupation. The mention of the site in several

historical sources for the Roman period on the one hand, and

the limited extent of architectural remains discovered in

the excavations on the other, invite us to examine further

the reasons for its historical importance at this time. As

the central site for primary and secondary glass production

on the coastal plain in the Byzantine period, we intend to

map all the furnaces discovered at the site in order to track

chronological sequences and chemical compositional differences.

We also intend to continue unearthing specific elements of

the Crusader castle (such as the moat and several halls) for

better understanding of its architectural plan. Furthermore,

we intend to conduct surveys and underwater excavations in

both the sheltered anchorage and the built harbor with foreign

institutes from abroad.

OUR 2012 AND 2013 SEASONS OF EXCAVATIONS

The Crusader Town of Apollonia/Arsur in Israel: Structure - Cultural Adaptation - Urban-Rural Relations

A project funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) "The Crusader Town of Apollonia/Arsur (Israel): Structure - Cultural Adaptation - Urban-Rural Relations" began in May 2012, as the fruit of collaboration between the University of Tuebingen (Germany), headed by Prof. Dr. Barbara Scholkmann and Tel Aviv University (Israel), headed by Prof. Oren Tal. Given the broad range of new cultural impulses the Crusaders experienced in their new environment in the Holy Land, this project aims at a better understanding of the European and local cultural influences that dictated the structure and organization of the town of Arsur and its hinterland. Muslim Arsuf was conquered by the Crusaders in 1101 and re-conquered by the Mamluks in 1265. The presence of the Crusaders left its mark on the town. Large parts of it were re-planned, while extensive fortifications, private and public buildings, as well as a castle were erected. The town’s abandonment after its Mamluk destruction led to a unique archaeological setting in which the Crusader layers were left largely undisturbed by later settlement activities and thus are highly suitable for intensified archaeological research. These layers will be the object of extensive light detection and ranging (LIDAR) analysis as well as geo-magnetic surveys, which will allow the reconstruction of the original topography and the design of the entire medieval town by detecting the layout of structures still hidden below the ground. These non-invasive investigations will be accompanied by two seasons of archaeological excavations in August-September 2012 and 2013. The finds from the excavations will complete the picture gained through the surveys by allowing insights into the material culture and daily life activities of the town’s inhabitants. The results of prospecting and excavations will be combined and compared to the site and its hinterland past findings, as well as to other contemporary medieval towns in the East and West, given the site’s cultural conglomeration of various social and economical transformations. This scientific work is to be carried together with PD Dr. Hauke Kenzler and Annette Zeischka-Kenzler, MA (researchers the University of Tuebingen) and Dr. Elisabeth Yehuda (a post-doctorate student of Tel Aviv University).

Die kreuzfahrerzeitliche Stadt Apollonia/Arsur in Israel: Struktur - Kulturadaption - Stadt-Umland-Beziehungen

m Mai 2012 wird in Apollonia ein durch die DFG finanziertes Projekt mit dem Titel “Die Kreuzfahrerstadt von Apollonia/Arsur (Israel) Struktur – Kulturadaptionen – Stadt-Umland-Beziehungen“, begann. Dieses Vorhaben ist ein Gemeinschaftsprojekt der Universitäten Tübingen und Tel Aviv unter der Leitung von Prof. Dr. Barbara Scholkmann und Prof. Oren Tal. Die moslemische Stadt Arsuf wurde 1101 von den Kreuzfahrern erobert und fiel 1265 wieder an die Moslems zurück. Über hundert Jahre fränkische Anwesenheit prägten die Stadt entscheidend: großflächige Areale wurden neu geplant und massive Fortifikationen, private und öffentliche Gebäude, sowie eine Burg wurden errichtet. Mit der Eroberung des Heiligen Landes wurden die Kreuzfahrer nicht nur Herren eines fremden Landes, sondern sie waren fortan auch einer Vielzahl an neuen kulturellen Impulsen ausgesetzt, die ihre europäisch beeinflusste Sachkultur maßgeblich veränderten. Dieses Projekt wird sich deshalb intensiv mit der Erforschung derjenigen Kultureinflüsse befassen, die die Struktur und Organisation der kreuzfahrerzeitlichen Stadt und ihres Hinterlandes prägten. Der Stadthügel von Apollonia/Arsur ist ideal für ein derartiges Vorhaben. Die Aufgabe der Stadt direkt nach der moslemischen Eroberung führte dazu, dass die archäologischen Schichten der Kreuzfahrerperiode größtenteils von späteren Störungen verschont blieben. Damit sind diese Schichten für großflächige archäologische Untersuchungen zugänglich und werden eingehenden geomagnetischen Prospektionen und Sondagen durch Georadar unterzogen. Die flächendeckenden Untersuchungen erlauben die Erstellungen eines digitalen Höhenmodells sowie die Rekonstruktion des gesamten Stadtplanes durch die Erfassung noch im Erdreich verborgener Strukturen. In einem nächsten Schritt werden zwei Ausgrabungskampagnen im August/September 2012 und 2013 stattfinden, deren Funde und Befunde wertvolle Aufschlüsse über die materielle Kultur der Bewohner Apollonia/Arsurs geben können und somit erlauben werden, das tägliche Leben in dieser Stadt zu rekonstruieren. Abschliessend werden die Ergebnisse von Prospektionen und Ausgrabungen durch die Resultate früherer Untersuchungen in der Stadt und ihres Hinterlandes ergänzt und derart vervollständigt, dass die mit Hilfe der Wissenschaft neu erschaffene, mittelalterliche Stadt Apollonia mit zeitgleichen Städten in Europa und im Vorderen Orient verglichen werden kann. Auf diese Weise wird es erstmals möglich sein festzulegen, welchen Kultureinflüssen eine fränkische Stadt im Heiligen Land ihr Erscheinungsbild zu verdanken hatte. Dieses Gemeinschaftsprojekt wird von Annette Zeischka-Kenzler MA, PD Dr. Hauke Kenzler (Universität Tübingen) und Dr. Elisabeth Yehuda (Universität Tel Aviv) durchgeführt.

Publications

Monograph

Roll, I. and Ayalon, E. 1989. Apollonia and Southern Sharon:

Model of a Coastal City and its Hinterland. Tel Aviv.

(Hebrew).

First Final Report

Roll, I. and Tal, O. 1999. Apollonia-Arsuf: Final Report of the Excavations. Volume I: The Persian and Hellenistic Periods (with Appendices on the Chalcolithic and Iron Age II Remains). Tel Aviv University, Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology 16. Tel Aviv

Collective Studies

Roll, I., Tal, O. and Winter, M. eds. 2007.The Encounter of Crusaders and Muslims in Palestine as Reflected in Arsuf, Sayyiduna 'Ali and Other Coastal Sites. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz HaMeuchad (Hebrew).

Tal, O. ed. 2011. The Last Supper at Apollonia: The Final Days of the Crusader Castle in Herzliya. Tel Aviv: Eretz Israel Museum. (Bi-lingual Hebrew/English).

Specific Researches

Ashkenazi, D., Golan, O. and Tal, O. 2012. An Archaeometallurgical Study of 13th-Century Arrowheads and Bolts from the Crusader Castle of Arsuf/Arsur. Archaeometry 54/6.

Amitai, R. 2005. The Conquest of Arsuf by Baybars: Political and Military Aspects. Mamluk Studies Review 9: 61-83.

Birnbaum, R. and Ovadiah, A. 1990. A Greek Inscription from the Early Byzantine Church at Apollonia. Israel Exploration Journal 40: 182-191 .

Fischer, M. and Tal, O. 2003. A Fourth-Century BCE Attic Marble Totenmahlrelief at Apollonia-Arsuf. Israel Exploration Journal 53: 49-60.

Freestone, I.C., Jackson-Tal, R.E. and Tal, O. 2008. Raw Glass and the Production of Glass Vessels at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. Journal of Glass Study 50: 67-80.

Galili, E., Dahari, U. and Sharvit, J. 1992. Underwater Survey along the Coast of Israel. Excavations and Surveys in Israel 10: 160-166.

Galili, E., Dahari, U. and Sharvit, J. 1993. Underwater Survey and Rescue Excavations along the Israeli Coast. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 22: 61-77.

Galor, K., Roll, I. and Tal, O. 2009. Apollonia-Arsuf: Between Past and Future. Near Eastern Archaeology 72/1: 4-27.

Grossmann, E. 2001. Maritime Tel Michal and Apollonia: Results of the Underwater Survey 1989-1996. BAR International Series 915. Oxford.

Kahane, P. 1951. Rishpon (Apollonia); B. Bulletin of the Department of Antiquities of the State of Israel 3: 42-43 (Hebrew). [English summary is found in Perkins, A. 1951. Archaeological News: The Near East. American Journal of Archaeology 55: 86-87].

Kaplan, E.H. and Kaplan, B. 1975. The Diversity of Late-Byzantine Oil Lamps at Apollonia (=Arsuf). Levant 7: 150-156.

Raphael, K. and Tepper, Y. 2005. The Archaeological Evidence from the Mamluk Siege of Arsuf. Mamluk Studies Review 9: 85-100.

Roll, I. 1996. Medieval Apollonia-Arsuf: A Fortified Coastal Town in the Levant of the Early Muslim and Crusader Periods. In: Balard, M. ed. Autour de la première Croisade. Actes du Colloque de la Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East (Clermont-Ferrand, 22-25 juin 1995). Paris: 597-606.

Roll, I. 2006. Apollonia-Arsuf: A Coastal Town of the Eastern Mediterranean Shore in Early Christian and Byzantine Times. In: Harreither, R. et al. Akten des XIV Internationalen Kongresses für Christlische Archäologie. Wien: 681-685.

Roll, I. 2008. Der frühislamische Basar und die Kreuzfahrerburg in Apollonia-Arsuf. In: Piana, M. ed. Burgen und Städte der Kreuzzugszeit. Petersberg: 252-262.

Roll, I. and Arubas, B. 2006. Le château d'Arsur: Forteresse côtière pentagonale du type concentrique du milieu du XIIIe siècle. Bulletin Monumental 164/1: 67-81.

Roll, I. and Ayalon, E. 1987. The Market Street at Apollonia-Arsuf. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 267: 61-76.

Roll, I. et al. 2000. Apollonia-Arsuf during the Crusader Period in Light of New Discoveries. Qadmoniot 33: 18-31. (Hebrew).

Roll, I. and Tal, O. 2008. A Villa of the Early Roman Period at Apollonia-Arsuf. Israel Exploration Journal 58: 132-149.

Roll, I. and Tal, O. 2009. A New Greek Inscription from Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf / Sozousa: A Reassessment of the Eis Teos Monos Inscriptions of Palestine. Scripta Classica Israelica 28: 139-147.

Shachar, I. 2000. Greek Colonization and the Eponymous Apollo. Mediterranean Historical Review 15/2: 1-26.

Sussman, V. 1983. The Samaritan Oil Lamps from Apollonia-Arsuf. Tel Aviv 10: 71-96.

Tal, O. 1995. Roman-Byzantine Cemeteries and Tombs around Apollonia. Tel Aviv 22: 107-120.

Tal, O. 2000. Some Notes on the Settlement Patterns of the Persian Period Southern Sharon Plain in Light of Recent Excavations at Apollonia-Arsuf. Transeuphratène 19: 115-125.

Tal, O. 2009. A Portable Sundial from Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf / Sozousa? Semitica et Classica [formerly Semitica] 2: 91-96.

Tal, O. 2009. A Winepress at Apollonia-Arsuf: More Evidence on the Samaritan Presence in Roman-Byzantine Southern Sharon. Liber Annuus 59: 319-342.

Tal, O. 2010. Apollonia-Arsuf 2006, 2009. Israel Exploration Journal 60: 107-114.

Tal, O., Jackson-Tal, R.E. and Freestone, I.C. 2004. New Evidence of the Production of Raw Glass at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. Journal of Glass Studies 46: 51-66.

Tal, O. and Baidoun, I. 2010. A Hoard of Mamluk, Ottoman and Venetian Coins (Fifteenth to Sixteenth Centuries) from Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. Numismatic Chronicle 170: 484-493.

Tal, O. and Taxel, I. 2012. Socio-Political and Economic Aspects of Refuse Disposal in Late Byzantine and Early Islamic Palestine. In: Matthews, R., Curtis, J., et al. Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 12-16, April 2010. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. Pp. 497-518.

Tal, O. and Teixeira Bastos, M. 2012. Intentionally Broken Discus Lamps from Roman Apollonia: A New Interpretation. Tel Aviv 39: 105-115.

Wexler, L. and Gilboa, G. 1994. A Signet Ring from the Apollonia-Arsuf Excavations. Tel Aviv 21: 288-291.

Wexler, L. and Gilboa, G. 1996. Oil Lamps of the Roman Period from Apollonia-Arsuf. Tel Aviv 23: 115-131. |

|

|

|